News

Recyclist w/ Danny O: Recycling Into the Record Books

Diamond Scientific teams up with Danny O., a world-renowned artist who uses his talents to impact the world in a positive way by championing the Recyclist cause. Below is the transcript of the 2/9/24 interview with Danny O., Ramon Rivera, CEO of Diamond Scientific and Eric Provost, the Recyclist’s podcast host, and Marketing Director of Diamond Scientific. Click HERE or visit DiamondSci.com to hear the interview in its entirety.

Eric Provost: Hello and welcome to Recyclist. I'm your host Eric Provost and today we are being joined by an incredibly special guest from Danny O Studio, artist, veteran and Guinness World Record holder Daniel O'Connor.

Danny, thank you so much for doing today on the Recyclist podcast, and we'd also like to welcome Mr. Ramon Rivera to the show.

Ramon Rivera: Thank you Eric. It's such a pleasure to be here and exciting because we've got Danny O. present, and I was so interested in his background and what he's done in terms of recycling efforts and using his art that I wanted to be present.

Eric Provost: And for those who don't know about you, Danny, and the stuff that you've done, give us a little bit of background because you're an artist by trade, but you've been doing this for a long time even dating back to your days in the military,

Danny O.: Correct. Right. That's right. Well, thank you both for inviting me, too, because this has been an interesting story, the one we're going to revisit.

But from the very beginning, when I was in high school, my sister was sick with cancer. And as a result, my brother Charlie and I pretty much did not go to high school. And at that time, the well I did, I went to the school, but I only went to The Art Room. And so by the time I got out of high school, I didn't have the grades for college. But I did test well in the Navy.

I tested well visually, which got me a job of Photo Mate. So I joined the service as a photographer from 81 to 86 was like a five-year tour, but while I was doing it very soon into my I was probably only in a little over a year. And my art got more notice than I was.

I was a good photographer, still am a good photographer. But the art leapfrogged and I became a Navy artist. It's just what I do, different ways that I do it.

Eric Provost: Apparently enough to get recognized by a certain Admiral. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Danny O.: I like that story. It's my best Navy story, perhaps.

So, I tried to paraphrase it down, but so I get on, I get in the Navy, I get on an aircraft carrier. And I'm a photographer and I'm on shoot crew, which means I'm one of the three guys that goes around and only makes pictures during the day.

And then later I start at night, I start doing a lot of cartooning and my own artwork because I noticed that a lot of guys, it's a 12 on 12 off and the guys on their 12 off were sleeping. And we had a seven-month cruise, and I was like, I'm not gonna sleep. I'm gonna distill down my sleep and I'm gonna maximize my own personal growth.

And they had a gym. So, I went to the gym. Nobody used it. There were 5000 guys on the ship. Almost no one used it, just the same four or five of us.

And then after that I went upstairs, and I started working on these cartoons. Then I get noticed within the command.

We made a yearbook, which is like the school yearbook, but it was a cruise book. And I started making all the cartoons for the cruise book.

Well, when the cruise is over, we go to all these different ports all over. It's an amazing tour. And then the ship pulls into the Norfolk Dry docks. We're in one day and my neighbor, who is a Yeoman, asked if I want to go for a ride. I had the day off. I went with him.

We go to this building. There's a civilian, a GS13, beyond the door. His name is Gordon Rawlings, and Gordon changed my life.

I asked to bring it and show it to someone else. I get invited up and yeah, I meet the Admiral who's in charge of every ship on the East Coast. And he says, with this all happening at the speed that I'll tell this story. I walk in the room. He shakes my hand. He says “Seaman O'Connor, your work, it's great.”

He's got it. He's got it in front of you know, Gordon showing me, you know, “Listen, would you like to work for me?”

I say “Yes, Sir.”

He picks up the phone, calls my ship. He asked my Warrant Officer. He says Warrant Officer, “Hey, does Seaman O'Connor work for you?”

He says “Yes Sir.”

“Seaman O'Connor works for me from now on. You understand that?”

“Yes Sir.”

Hangs up the phone, shakes my hand, gets me out of the room. I worked for the Admiral. I was his driver. I was his cartoonist.

It was like, and then my story from there went into art in other ways in Virginia Beach. 17th St. Surf Shop. But that's initially how I got started.

And then I just I had these amazing opportunities when I was really young where people gave me a lot of credit and opportunity with my talent. Surf Shop was one that was happening the same time as this Admiral.

I lived a life where I got to see what art could do, and I used the art quite often to create the life that I wanted, not the other way around.

Ramon Rivera: When Danny shared that story about the Admiral, that's when I said he's got to come on.

Eric Provost: But I mean we are the Recyclist podcast, this is you know about conservation and the environment. So one of the reasons that we wanted to bring you on is you have a fairly unique take on conservation and I think people would kind of be interested in how you approach that.

Danny O.: Somewhere in the 90s, one winter I spent a lot of time in my studio and by spring I knew that I was unhealthy and that I was enough to figure it out, but I was smart enough to know that I needed nature.

That was what this internal healing call for me was that you need to be outside. You can't live your life in the studio making art. It's not going to work. And I had a lot of work at the time, so that's all I did.

You know, I had a lot of jobs, so I was a portrait painter at the time. So, I just, I just painted, painted, painted all the time. And it made me unbalanced. So, I started going on these walks and there were other things going on in my life where trust was an issue, where I was dealing with trust and how to overcome trust, how to trust myself. And how to hear that, that inner guidance. And I really, truly wanted to exercise and grow that muscle more than the art because I didn't feel like I had a connection to it.

So, I started walking along the edges of Boston. Long because I lived in Chinatown in Boston, and I would go on these walks, these meditation walks, and at first, I collected a lot of things. And I saw myself as like the Beachcomber collector. And I grew up on Nantasket beach, right on the water. And I always had a very spiritual connection to the beach.

And when I was young, I felt like the beach was my artistic master, if that's not too grand. We would come to the ocean in the spring and the beach would be a mess.

Well, some people would see it as a mess. I particularly was, and my brothers were. We were my sisters too, less than. But my brothers and I, we would drag stuff for a half a mile and build forts, and we would drag stuff throughout the winter. And it was the greatest form of beachcombing finding and the amount of crap that we would drag from, like, seriously, you know, it's like alphabet streets from A, we lived on Q, well beyond A. We would drag it all the way down and we had our boards and by spring. The board, there would be a whole cluster of all the kids in that area had grown this thing and then they'd come, and they'd clean the beach.

So, as I get older. I'm at the beach one summer and I noticed the plastic and the wash up hasn't been cleaned up like they don't have that service anymore and I was always fascinated by beach wash up.

And so, I started collecting all the number two plastic and bringing it to our family home, which was on the water and in the basement had these big plastic bags. And I was like giving some sort of order to this stuff and perhaps it had a higher value because it was, you know, so I loved collecting that, you know, so there was a bag of green, a bag of red, a bag of yellows.

And I know that no one really spoke to me about what I was doing, but I think they thought I was crazy. You know, I'm like trying to, like, find order or something on the beach.

And I collect quite a bit of stuff, but I had it ordered, so I thought it had. And I looked at it when they were in the bags. It was kind of beautiful. All the different greens was like gorgeous. Something about it was like it kept feeding me to not stop.

So, when I go back to Boston, I start walking on the waterways of Boston. I do the same thing I do on the Charles River. And then I make some pieces out of the work, and I take it to New York City, and I show Alex John, who was never really a formal teacher of mine, but probably my greatest adult Mahatma that I came across that was human and I shared these works with him, and he lived right across. I was going to Cooper Union, and he lived across the street at Cooper. Fantastic story.

He saw them and he was like. "Dan, no, no, it's terrible."

Now, Alex was the most supportive being ever, and he had never said anything to me. So, I was like, wow, Alex. So, I took those pieces, and I was very, you know, I traveled down there on a Greyhound bus with a Dolly in Times Square. I had these things stacked up, and I wheeled them down to the East Village. So, I put them back. I go back.

But I loved Alex, and Alex was the truest of the true in my life. And so, I took them back. I got back to Chinatown. There was a dumpster. I got back at like 3:00 in the morning. Threw him in the dumpster. Covered them so no one would find them because there were other artists.

All the artists we dumpster dive like crazy. That's how I made a living. And I went back to the studio, and I thought, what is the thing that I can say that I can keep collecting because these, these meditation walks are very healthy for me.

So that's another part of the story where I said, you know, I felt unhealthy. Now I'm out getting a lot of air. I'm working on my balance because I'm going rock to rock all the time. It's very slow and I'm meditating the entire time or I'm chanting the entire time.

So, as I was doing this, I also, I felt like this job was given to me. And I knew this job was given to me, not through spirit or through some. I didn't invent it. It sort of happened upon me.

So, I started collecting balls, because they're the most beautiful. Of the found objects, it's a sphere, and within the sphere, everything comes as a sphere.

The Earth, you know, it's symbolically the most beautiful of the shapes that I could find. And I had been collecting pencils, pens. You name it, I collected it. And so, to discard all that and I only collected the balls.

Then something really amazing happened because I was also really trying to tune into my own intuition. And I started to find these things like crazy. And I'd go in. I was waiting tables at the time, and I'd go in, and I'd tell people “How many balls do you think I found today?”

And they're like “Found? Did you take them? Did you take them somebody's

backyard?”

I'm like, “No. Pure finds. How many did I find?”

“12?”

I'd say “No, I found 76.”

Eric Provost: What?

Danny O.: Yeah, I went to do my laundry down in Charles St. and here's the thing, though. I had learned that during a flood or heavy rain, the Charles River would float up a couple inches, right? And the balls that would come down from the tributaries, from Waltham and all these Lynn, all these other places would come, and they get stuck in the reeds. And all I would have to do is go through, and you couldn't do it seasonally. It had to be best in the fall when the leaves were down or spring before the growth. After the growth, everything is green. You can't see anything.

So, I always worked, I worked off months but the ball thing. Then I started to invite people to come do it with me to see what are the chances that I could turn this into, like if I can find 100, does 12 people make 1000? And sure enough, whenever I took people on these trips. We would pick something on the map because I started to follow the tributaries. Well, this might be a good spot. A swamp is actually a very good spot. Not to bring your friends, but to have ball finding anything.

So, then there'd be 12 people out, you know, We'd find these desolate areas. No one would ever go. The only reason I added people to doing it was that this curator from the decorative museum, Nick Capasso, came into my studio to see my paintings and he was immediately, like, asking me. “What's this?” And I tell him the story and he couldn't even see the paintings. You know, it was he was just like, “Wow, this is what I want this in the museum. Could you do this and put it on a wall?”

And of course I was, I had only one bucket. And I was like, “Oh, yeah. Oh, yeah, I can do that.” in my mind. I'm like, ‘Oh, yes, I can. I can do that.” I couldn't. I didn't, you know. But you know, it was my first museum show. So, I gathered my friends, we started doing it, and I just became obsessive about it, because with this project was coming. A lot of press, a lot of articles. TV. It was nutty and it wasn't. And even then, I knew this isn't my art. But this is a shot, and this is legacy. And go for it, you know, Go for this story. Go for leaving something behind and who knows what happens in between.

One of the best stories from that museum, though, it was, it was on these this stairwell, right. So, it was about four stories up. I don't know man, maybe 30-40 people helped me assemble it. We always made it a party, but we assembled these panels. We take them to the museum. We assemble it, and I leave and then I start getting calls from the preparator that the balls are dropping off.

A ping pong ball falls and breaks open. Now this ball had been floating in the Charles River for, I don't know, 15 years. When that thing broke open, the water stunk so bad, they closed the museum down and they called me and they're like, you need to take this thing down. And we can't have this because they smelled so bad. It was like egg drop soup. They were furious.

So, they give me this room and then for two weeks, me and JJ, who's now a very good painter, screwed like, like hundreds of screws into the balls. And the whole time I'm just sweating balls. Like so much adrenaline of like, oh, I lost my opportunity, my one shot and I blew it, and I wasn't, you know, I wasn't prepared for anyway, we fixed it. We put it up. It lasts long enough.

But one of the saving graces was that I was a waiter, you know, so who I got along with best was the security guards. So, they really liked me a lot. And every time I went to the museum, they would be like dead, and they give me a box and it would have all the balls that had fallen off that they didn't tell up the chain of command. And that was like, I don't know, you know, it, it saved me.

So, from there it came down and then it went to MASS MoCA, and at MASS MoCA it really grew. They invited the world to come, you know to see their museum.

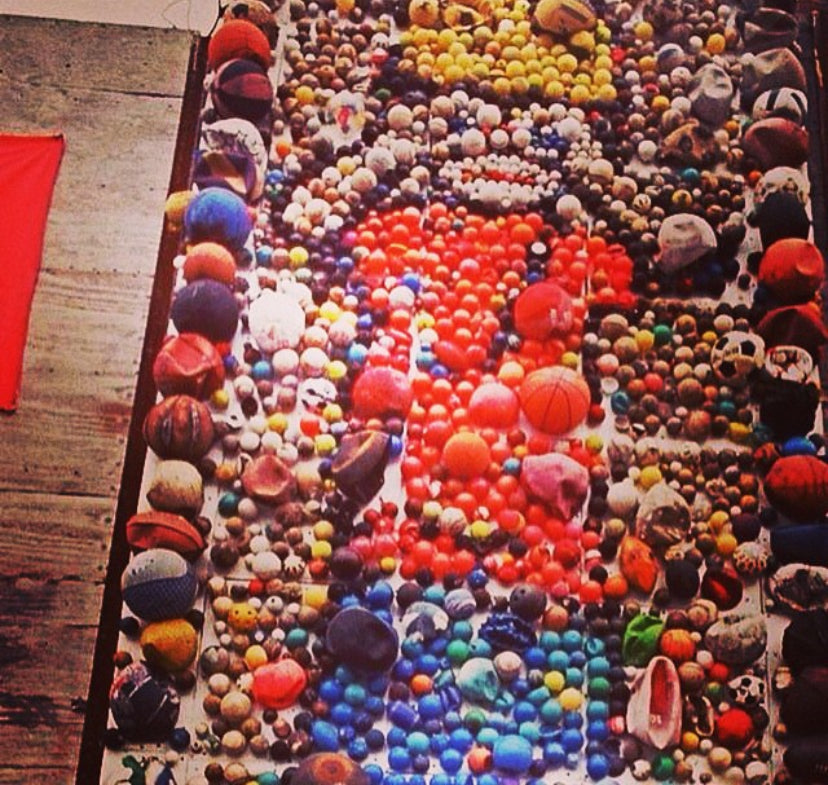

But I was part of a show called Game Show. So, you were allowed to play Danny O’s ball game and bring balls. And by the time that it was there for a year, that's where I got the Guinness Book of World's record. And by the time I left over 6000 balls had been donated, mailed and sent to MASS MoCA and they had a huge cage outside, and they continued to fill. And then from there I did it with the band Fish and then after that it, it slowly dismantled.

Eric Provost: Something that I definitely wanted to ask you about as you kind of touched on it briefly, just kind of glossed over the fact that you are in the Guinness Book of World Records. Some people may be wondering about the scope of this project, where you find just discarded items on the beach or the riverbed or something, but you collected enough of it to get you into the Guinness Book of World Records. Specifically, what did they annotate you as? What was your exact record?

Danny O.: I'm going to tell you this story behind why I got it. I think it's much more interesting, but my thing is Largest Ball Mosaic Made from Reclaimed Balls or something along those lines, 2005, but the story is that when I brought the balls to MASS MoCA they came with this fragrance, right? I mean, my studio reeked of river. It was nasty. I had a door open all the time.

So, when I brought it to the museum, it brought this scent with it and they weren't prepared nor did they like sort of that organic quality, but they wanted it to grow.

When I get it to MASS MoCA, around the piece, there was the piece that was there before me that the floor hadn't been totally cleaned. So, I said “I can clean this up”, you know, I should have let them do it, but I took it on.

They didn't have a huge crew at the end. They were in stumbling other things. Anyway, the maintenance department had given me glossy paint, not satin, so there was this glow of like rolled out. It was horrible.

So, then they have a meeting in the courtyard like 2 days later with the curator and everybody in the meetings wearing sunglasses but me. And they're glaring me down, like “You screwed up the museum!”, you know?

And then from that moment on, the curator just never spoke to me ever again. That hurt too, cuz I was like, I'd be in the museum, I'd be working on my piece, she'd be talking to, like this German artist and like and I wouldn't even be like, “Hey, and this is another one of our artists.” It was just like I got iced.

So, the show is called Game Show. So, I said, “All right, you know what? I'm gonna win, I'm gonna win Game Show. I'm gonna get a Guinness Book of Worlds record for my piece.”

And so, I researched what it took to get one. And really all you have to do is create a category and then it should be something, you know something, interesting. And I thought I had something interesting enough and then I asked the mayor to officiate the count and you know I got it.

I went down the list of what it took to get it and it wasn't that difficult. And then when I got the Guinness Book, every paper in the region, it was absolutely bananas. The whole top fold, “Local artist gets Guinness Book.”, and then flipped down and there was a huge picture.

People were calling me. It was like it was the weirdest thing because I knew it was just a hook. It was a trick. It wasn't like. And it still is with my kids, I think you know. Which leads to this other cap project, you know.

Eric Provost: So, congrats again on the world record. But in recent years, how has this project, the ball reclamation art project and other types of found object art, how has that evolved and have you still been working with it?

Danny O.: When I worked on the balls, I considered myself as the organizer of the ball family reunion and if there was a ball in my vicinity, I found that I could track it.

From the time I got the Guinness Book, I turned my back on it because it was incredibly labor intensive. There was a lot of bending over, picking up. There was a lot of sorting.

I had to rent a barn, a barn to store them. And if you can rent A U-Haul truck, the largest truck, that's what it took to move them. Packed not like a couple of some boxes in, but I stacked up the front all the way to the back. It was filled.

That was exhausting. So, I put it away for many reasons because I thought that my bigger goals, it was as though I could have been doing that. I was invited to be on TV, like on Letterman, and like how far back it was at Letterman?

But it was like all those shows, they bring me in to do a reel, but I couldn't put the words together. And there were all these producers talking to me. I was like, whoa, I had a complete appreciation for what actors go through.

But umm, in recent years. I've meditated on that while I collected balls, the other thing that I saw when I was out there all the time was plastic caps and I would ignore them. But there was another family, and I was always watching them because they were migrating with the balls, right? The bottles were not.

That was what was haunting to me. There were all of these plastic caps, and they were all so beautiful right there round. They're colorful, they're different sizes. And all the time I'm watching, looking for just the balls, I would see that. And I would think, well, there's a whole other body of work there some other time. But I've never returned to that because there was a certain obsessive quality that was happening in that drive to make that success that really affected my mind and I didn't want to do that anymore, like that much.

The obsession, the for quest for success was a bad combo. So even though I went out trying to find inner balance, I overused it. And then, you know, and then I realized. And now I'm a lot more balanced, I think. But when I look back and I think about the plastic that I saw, I have my own collection because I just like seeing them grow.

And then different times I've taught in school systems where I'll be like an artist-in-residence, and I share this project. So everyone in the school saves plastic, saves the caps. And then in each class they found a different way to talk about it.

In math, the ratio like why is it that yellow is such a scarce of all the colors. At the end of the month, you can see there's not a lot of yellow. Very interesting, there's more green, there's a lot of white. So, there are different ways in all the different classes where they could find a way to talk about it. And then with them, I had, because I had a workforce now, I would only talk about it, and they would do it. So, I would say, “OK, let's order all the colors.”, and in like 7 minutes these thirty kids would organize all the colors, all the caps. And then I'd say, “Let's make a fish.”, and they would start one end and then before you know it, they'd have a fish.

And it was the interesting part of them playing with them. It was almost like Legos. It was almost universal because when I looked around and when the teachers looked around there wasn't a kid who wasn't somehow involved or, like you know, that nobody seemed to be bored not to brag on the project. But it had a way of triggering imaginations with just caps, which was kind of fascinating.

And so that's the way that I've shared it and I've often, and part of the podcast is that, in thinking about what I was going to talk about is that I know that I'm not the one to be going out collecting them. I think I'm the one to talk about “Hey, maybe you should, and what happens if you did, and what would happen if you did it in your community?”

And when I talked to Ray about it, about the cap specifically, because I also have had some time when I've dove into the cap project that I think it's a community thing.

If a community adopted it and built it, anybody that saved a cap along the way, one cap, 10 caps, 50 caps. And then the goal is you get a Guinness Book of World's record because it's very easy to do, right? The biggest blank made out of caps.

You know, you do the biggest library emblem made of caps or whatever it might be. And then everybody that participated gets a Guinness Book of World record.

I always thought it would be a cool project where everybody in the town saved, then everybody would, you know, be able to share that collectively.

Eric Provost: And at the absolute worst, it would be cleaning up the environment and helping clean the community, right?

Danny O.: Right.

Ramon Rivera: I was traveling in a little town called San Pancho, Mexico. I was telling my wife the other day about meeting you and she says, “did he do that one in Mexico?” And it's a mural made of caps. It's a recent mural. So, you know, my assumption is that they'd seen that art form somewhere.

Danny O.: Oh, yeah. I didn't invent it.

Ramon Rivera: Yeah, they'd seen that art form somewhere. And they said, oh, let's do this. And for me, you know, with my history. In the recycling business, I just was so intrigued. Hearing your story, trash can be beautiful too.

Danny O.: Oh yeah,

Ramon Rivera: And it sustains a lot of people. You know, recycling sustains a lot of people. Not only in your case an artist, but, you know, remove people that actually collect it, process it. And so, the movement for, you know, people to get excited about saying, hey, let's save that piece of plastic and put it in a recycle bin, you know, your awareness I think has made a difference.

And that's the back-end story for me. Because as an, you know, as an operator, a guy that ran a, you know, recycling. Transfer station, solid waste, a collection side of the garbage side. You know, for me what you've done is you built awareness through all your work. And that's to me more important than anything.

Danny O.: The beautiful thing is that since I've done these projects, people will e-mail me or they'll see something out. Like my kids sent me pictures from Maine where they saw a shed that was covered and it was almost like, well, they're doing it better than I, you know.

And in different places too in these beautiful lawns where I'm like, “Oh yeah, they took it.”, but I think they're beautifully done and there's some that take them apart.

I mean it's extraordinary what some people do. I knew I had a legend to create in a window of time. And I dedicated that time to it.

But I also knew walking amongst trash all the time took, it took a heaviness to, like there was a heavy, it wasn't always light, you know. Sometimes I come away like, I don't want to do that forever.

Ramon Rivera: So, the moment you started this walk, this journey, we were just starting recycling in the United States. I mean, historically retail establishments collected cardboard, and there was some glass efforts, but plastic had become a big part of a consumer’s waste problem, right?

So, all of a sudden, we have this plastic, we don't know what to do with it. So, artists like you in that time period, especially in the 90s, built this awareness around, you know, there's other options here. And by the way, just picking it up at the beach, you know, was a worthy endeavor.

Danny O.: You know, cleaning up your hand can be playful.

Ramon Rivera: And it can be playful. That's right. So, I think that you deserve a lot of credit. And you could probably walk those beaches today and as a result and those tributaries that you walked and they're going to be much cleaner today.

I expect they would be because of the awareness you developed back in those early years just through your art form and through your personal caring. So that's really, I think what's really important here.

Danny O.: If I had any effect like that, that's strange. I don't know how to take that because when I did it, it wasn't for that, but I have learned. That life is, you know, you throw something that that pebble, that ripple effect, how it can grow and I have seen other things that I've done in art and how those have grown over time were in ways that I couldn't believe, you know.

So, there's one more person I want to mention. His name is Michael Davies. He was a Canadian artist who was collecting balls at the same time as I was for the same reasons drawn to it. And when we met, when we shared stories, I don't know how to describe it but he was so, like-minded. That in that time we both knew that we didn't come up with these ideas we were just following.

And I knew that the whole time that this wasn't my thing I would just somehow taking direction and I was going to follow it. But Michael was the same way, and he added a lot to the piece at MASS MoCA and he's a terrific artist too.

Eric Provost: Well, allow me to extend to thank you as well for joining us today on Recyclist. Absolutely fascinating story and again I will make sure to plug your Instagram so people can go and see all the great work that you've done. Thank you for sharing your story with us.

And if you'd like to see more of Danny O, you can follow him on Instagram at @Dannyostudio1963. And you can also reach Diamond Scientific online at DiamondSci.com or call them at (321) 223-7500. Thank you all so much for listening. And we'll see you back next week for another episode of Recyclist. Thank you.